The art of putting your paintings in familiar surroundings

By Richard Nalley Forbes fyi Magazine

FALL 2003 Cover and Pages 88-90

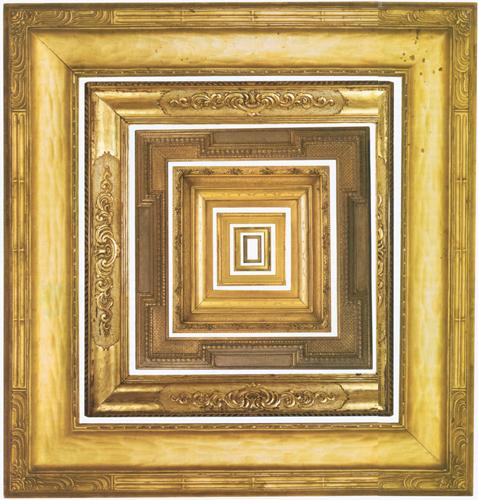

Here’s the shocker ending to the murder mystery I may write someday: The loot everybody’s scrambling for is concealed in plain sight. It’s the collection of masterfully carved and ornamented frames around the pictures in the deceased man’s front hall. The paintings themselves might be sad-eyed clowns on velvet purchased at a parking lot art fair. Doesn’t matter. It’s the frames, Sherlock.

When you consider that an original gilded beauty by Herman Dudley Murphy from the early 1900s might fetch $275,000, or a modest-sized, signed example by Charles Prendergast $50,000, it wouldn’t take many frames to add up to something like real money. It may come as a surprise that anything so, pardon the expression, peripheral could command such sums. But to a whole art world insider culture of private collectors, dealers and auction houses, antique frames are themselves worthy of scholarship, connoisseurship and trophy hunting.

It was Edouard Manet – wasn’t it? – who said, “Without the proper frame, the artist loses 100 percent.” And he wasn’t alone in that feeling. Edgar Degas carried on a jealous cross-Channel frame-designing rivalry with James McNeill Whistler, and took the matter very seriously indeed. At one point Degas was said to have ripped a patron’s Degas painting off the wall and attempted to repossess it when he found that the man had changed the Degas frame.

Unfortunately for painters down through the centuries, the world is full of art patrons like Monsieur Degas’. “I think changing a picture’s frame is an ownership thing, a territorial way to put your mark on a painting,” says Eli Wilner, a New York dealer widely credited with raising the American frame market’s consciousness (not to mention prices). “Look at Napoleon: He refrained everything in the Louvre, and influenced Catherine the Great to do the same in Russia.”

We are standing in the offices of Eli Wilner & Company in Manhattan, a minor monument to Man’s Desire to Reframe. An Aladdin’s cave of gilded, compo’d, carved Stanford Whites, Foster Brothers and Thulins, Wilner & Co. rambles through a warren of brownstone rooms above a dingy Upper East Side deli. Security for the $30 to $40 million in artwork and frames Wilner estimates he has on hand at any given time is partly provided by the heavy steel door installed by the former tenant, an after-hours gambling joint.

These premises, plus the hangarlike 11,000-square-foot workspace Wilner maintains for his brigade of restorers in Long Island City, are a far cry from the walk-up apartment where he first lived and sold frames back in 1983. At that point buying antique and period frames was a ducks-on-the-pond racket, partly because he was one of the very few people who wanted them. “Galleries up and down Madison Avenue had basements full of discarded frames,” he remembers. “They’d say, ‘Eli, just take ’em.’ “

Wilner was then a few years out of school and filled with a young man’s wonder at the obtuseness of an older generation’s received wisdom. “Somebody,” he says, “was clearly missing the boat. And I just really didn’t think it was me.” And he was really right. That first year Wilner did a self-reported $200,000 worth of frame business out of his apartment.

By 1990 the Metropolitan Museum of Art, followed by numerous other museums, had begun to label its frames as well as its paintings. Dealers like Julius Lowy and Henry Heydenryk in New York, Gold Leaf Studios in Washington, D.C., and The Fine Art Society in London were doing a major trade in formerly forgotten period frames. And though neither of the Big Two New York auction houses hold frame sales per se, the scene had become much livelier in London, where, for example, Bonhams now schedules four a year concurrent with auctions of Old Masters paintings.

That has begun to dawn on certain people is partly that fine, old frames are beautiful craft pieces in and of themselves, and partly that the lovely oil painting they inherited from Aunt Gertrude would look a lot more at honk in the style and period of framing that first suited it to begin with. The 1960s frame dear Auntie put on the 1890s portrait gives it a mismatched look succinctly described by an expert on Antiques Roadshow as “sort of like dressing up a pig in a tutu.”

“The artists had the right idea originally,” notes art and frame collector Jim Dicke II, chairman and CEO of Ohiobased Crown Equipment Corporation, “but framing has gone through so many fashions that you can go to a museum and guess the era when a painting was bought for the collection, because the frame gives it away.”

So if one picture has had many frames over the years, logic would suggest that these older frames would be in plentiful supply, just as Wilner and others seemed to find 20 years ago. Sad to say, though, the piles of forgotten gems were rapidly depleted as the market woke up to their value. In fact, the stocks of old frames were actually never very big. “Until recently these frames were not seen as a valuable or interesting part of art history,” explains Alan Montgomery, head of the Frames Department at Bonhams, the London auction house. “So large numbers of them were altered, damaged or just destroyed.”

It is part of the story-bitter lore to today’s frame lovers – that many of the finest and most valuable frames were systematically rounded up to recover the gold content of their gilding. As recently as the 1950s a character called Frank the Frame Burner drove his horse and cart around London collecting castoff 19th-century gilt frames to melt down. Even so eminent a dealer as The Fine Art Society has its former “Old Gold Room” where decades of gilt frames awaited their doom.

The older frames that survived these perils have now considerably appreciated. The least expensive period frame offered by Eli Wilner & Company during a recent visit was a drab little (4″ x 5″) 19th-century black rectangle suitable, perhaps, for framing a pinned beetle, at $l,500. Still, it was on store giveaway compared to the operatic 3′ x 4′, $275,000 Hermann Dudley Murphy, or even a similarly tiny $12,500 gilded and ornamented American item from 1840. At Bonhams, better 18th- and 19th-century frames can sell for £8,000 to £10,000, and English frames are rapidly catching up in price with the traditionally pricier Continental versions. A Louis XIV-era French frame holds Bonhams’ house record at £25,000, or $40,000. (The apparent all-time record was for a carved amber mirror frame from late-17th-century Danzig that sold for $947,000 at Sotheby’s in the depths of the 1991 recession.)

Bargains are getting harder to scrounge up. “There are no obvious neglected areas in picture frames any longer,” says Simon Edsor, a director of The Fine Art Society. “The majority of those I’d describe as inexpensive are inexpensive for good reason: They’re not very nice.”

So what is nice in an antique frame? According to Edsor, being old is a big plus, but it’s best to be old from certain periods, notably the 18th-century French. “That’s largely because those frames work with such a wide variety of pictures, 18th-century right through the Impressionists and even certain modern figurative paintings. They have a separate class act about them.”

Beyond that, the condition of the frame is a huge determinant: Has it been cut down? Refinished or regilded? In Europe, the market has generally preferred hand-carved frames to those common in England and America in the 19th century, which were adorned with molded and applied ornament made from “compo,” a plasterlike composition material. In the U.S., where the 19th-century (and turn-of-the-loth) dominates the high-end market, pieces that are signed by certain makers or artists typically command the top prices.

Now, 20 years down the road, seer Eli Wilner has begun collecting American frames up to the 1950s. “They are still underappreciated,” he explains. “People still have not looked through their attics and basements.” (Memo to self: Send the man some Polaroids.)

In wistful moments, Wilner laments that the market for collecting period frames purely as art objects in and of themselves has never built up the head of steam he predicted. There are such collectors, though. Bonhams’ Montgomery recently visited a client whose living room wall was hung with six empty 16th- and 17th-century Spanish and Italian “tabernacle” frames, which are particularly complex and architectural.

Wilner’s client Justine Simoni of Pensacola, Florida, has gone far beyond that. Though she declines to estimate her collection’s value, Simoni will confess to having “about 200 frames, nearly all of them empty,” that cover the walls, and in some cases, ceilings, of her home. “I am so moved by frames as objects of beauty,” she says. “I have a concern that they will be cut down and pasted back together to suit the temporary needs of others who lack any feeling for them.”

The fact that so many people these days have developed that feeling bodes well for the future. And if it’s a little late to get in on the ground floor, there is still the satisfaction of being on one of the lower stories, the mezzanine maybe. Says Wilner, “The collecting of frames is still in its infancy, and that is cool.”

Get the Picture

Some notable period-frame dealers: Eli Wilner & Company, (212) 744-6521, www.eliwilner.com, and Julius Lowy Frame and Restoring Company, (212) 861-8585, www.lowyonline.com, both in New York; and in London, The Fine Art Society, (011) 44-20-7629-5116, www.thefineartsociety.com.

For a schedule of Bonhams’ auctions: (011) 44-20-73933900, www.bonhams.com.