Framing Beaux, An Essay By Mark Bockrath

Adapted from the Book by Sylvia Yount, Cecilia Beaux: American Figure Painter Published by University of California Press (August 1, 2007) An Essay By Mark Bockrath Pages 84-102

Picture frames have always had a profound aesthetic effect upon the works of art they house. While many artists throughout history have expressed a preference for certain types of frames, it was not until the nineteenth century that they commonly regarded them as an intrinsic part of their aesthetic statement. Frames that were previously intended to fit a painting into an architectural scheme, or to lend uniformity to a gallery of paintings of diverse styles, gave way to frames chosen, and sometimes designed, by the artists themselves. By the mid-nineteenth century, English Pre-Raphaelite artists such as Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–1882) and Ford Madox Brown (1821–1893) were designing their own highly individual and idiosyncratic frames; in subsequent decades, artists like James McNeill Whistler (1834–1903) and Edgar Degas (1845–1917) followed suit. Whistler’s later frames, with their austere stepped and reeded profiles, were widely emulated by his contemporaries. In 1868 the English art critic and designer Charles Locke Eastlake (1836–1906) wrote: “It is a practice with many artists of the rising English school to design their own frames for the pictures which they exhibit.”

The latter part of the nineteenth century also witnessed a wide variety of revival styles in cast composition ornament that included interpretations of French Louis XIII, Louis XIV, Louis XV, and XVI frames, Italian Renaissance and Baroque frames, and Dutch and Spanish Baroque frames. The American expatriate painter John Singer Sargent (1856–1925) used a variety of revival styles for his paintings; especially notable were frames inspired by seventeenth-century Spanish models. Sargent and many of his contemporaries, including Cecilia Beaux, also sometimes used antique Renaissance, Baroque, and Rococo frames for their works. These artists realized that the weight of the frame molding, the tone of the gilding, and the careful selection of carved and cast motifs from the prevailing revival styles were important considerations, given their ability to either complement or overwhelm paintings.

Frames of high quality and distinctive design appear on works throughout Cecilia Beaux’s career, reflecting shifting tastes and trends in style. But how can we be sure that any of Beaux’s works retain their original frames, or that any of these frames were chosen by the artist herself? No account of Beaux’s taste in frames appears in her autobiography, Background with Figures, and comments pertinent to this subject have not appeared in the Beaux literature to date. One might conjecture, however, that Beaux’s early training in design predisposed her to a taste for quality frames. Photographs showing Beaux’s paintings on view at the annual exhibitions of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts reveal frames that must have been of concern to her, given the importance of the venue for publicizing her work and garnering accolades and commissions. If the works displayed in these exhibitions were newly painted and not yet sold, one can safely assume that they were framed by Beaux. Restricting our survey to period frames, however, does not guarantee that we are seeing frames chosen by Beaux, as many paintings—portraits, in particular—are framed by their owners. In addition, paintings lose their original frames and are reframed with great frequency, sometimes early in their lives. Mother and Daughter of 1898 (cat. 57), now in a cast composition Louis XV–style Rococo Revival frame with center and corner cartouches and swept (curved) edges (fig. 67), appeared in the Sixty-ninth Annual Exhibition of the Pennsylvania Academy in 1900 in a gilded, straight-edged reverse molding (sloping away from the painting) that was probably its original frame (fig. 68). Both frames are of virtually the same vintage.

Fig. 67. Mother and Daughter (cat. 57) in its current Rococo Revival frame.

Fig. 68. Detail, installation photograph of the Sixty-ninth Annual Exhibition, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia, 1900. Beaux’s Mother and Daughter, in its original frame, is in the center. Archives of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia.

Finding similar frames on paintings of the same date, especially in different collections, can be helpful in finding trends in an artist’s framing. The appearance of a distinctive Arts and Crafts frame, such as the one on Clement B. Newbold (fig. 69), which also appears in replicate on several contemporary portraits, strongly suggests that Beaux had a preference for such frames. Old exhibition labels and inscriptions on the back of a frame may help us to determine its age.

The Early Works: Revival Styles and the Aesthetic Movement

The earliest frames Beaux used are high-quality examples of eclectic “Renaissance” designs, with Classical motifs in gilded cast composition (a kind of putty that can be pressed into molds to make ornaments) or designs that reflect Aesthetic taste. Beginning in England in the 1860s, the Aesthetic Movement represented a shift away from ponderous Victorian ornament to more refined designs frequently influenced by the ideals of Classical and East Asian art. Beaux’s early training in Aesthetic design is suggested by the frame for her watercolor Edmund James Drifton Coxe of 1884 (fig. 70). This early work is framed in a flat profile with low-relief casts of composition in trailing patterns of flowers and leaves on a textured background.

The trailing floral pattern, which reflects Japanese decoration, is commonly seen in Aesthetic design. The casts are highlighted with different colors of bronze paint, producing a rich effect; a textured yellow-gold background serves as a foil to the pale lemon-gold leaves and orange-brown flowers with brown centers and buds. Such low-relief floral patterns with copper-colored flowers are also found in Aesthetic silver. Furniture by Herter Brothers of New York in the Aesthetic style employed similar patterns of floral motifs in the form of inlaid wood.

A worthy, and probably original, period frame complements Beaux’s exquisite early portrait A Little Girl (Fanny Travis Cochran) of 1887 (fig. 71). Its wide reverse molding is ornamented with a series of composition castings that are accented with burnished gold leaf. The profile and its rich cast motifs recall Italian Renaissance and Baroque design and give the frame an individual character that distinguishes it from other contemporary Renaissance Revival or Barbizon frames. A most striking feature is the series of large lobes of burnished gadrooning (a row of angled ovals) that rake from the centers along the outer edge. Other motifs include an interior cove with palmettes and courses of large egg-and-dart patterns. The half-round knull (upper) edge, with its pattern of small flowers enclosed by straps, is especially Aesthetic in feeling. The richness of the surface and complexity of the design both mark this frame as a work of high quality and reflect Beaux’s taste for contemporary Aesthetic design.

Frames with Renaissance Revival motifs also appear on four Beaux portraits of Philadelphia bankers painted in the 1890s, now in the collection of the National Museum of Women in the Arts. The frames on two of these portraits, Joseph Townsend and Israel Morris (fig. 72), are similar in design and bear labels on their backs from the important Philadelphia frame makers and dealers Earles’ Galleries of 816 Chestnut Street. The other two portraits, T. Wistar Brown and James V. Watson, have frames with wide, canted, flat coves surmounted by large scrolling leaf casts on their knull edges.

An 1893 installation photograph of the Sixty-third Annual Exhibition of the Pennsylvania Academy shows Beaux’s The Dreamer (cat. 39), painted the same year, in a wide gilded frame with a scooped profile and edge ornamentation with Renaissance motifs. The painting is now in a narrower carved frame in the later Arts and Crafts style.

The frame for Les derniers jours d’enfance (cat. 9) was altered from its earliest complex Aesthetic design to its present simple twentieth-century form, probably decades later, after damage and loss to its cast composition ornament. Its nearly triangular profile and underlying carcass were left intact, but the frame was “modernized” by removing most of its original cast composition ornament. An early photograph of the artist seated before the painting (see page 84) shows the original ornamentation on the outer cove of what appear to be thistle plants alternating with acanthus leaves, with delicate floral castings and ribbon spirals on a torus (half-round) profile on the knull edge. The original gilded-oak interior cove is also visible in the photograph. This cast ornament was removed from the outer cove, leaving the gilded oak of the inner cove bordered by a course of beads and spindles at the sight (inner) edge. The outer cove was replaced by a broad molding that is painted black, and the knull received a small, gilded, half-round molding.

Gilded oak was popular with many artists from the 1870s to the 1890s, especially devotees of the Aesthetic Movement, for the subtle texture provided by gilding directly on the coarsely figured grain without an intervening gesso layer. The gilded-oak frieze was frequently associated with the English painter George Frederic Watts (1817–1904), who used it on a flat cassetta (Italian for “little box”) profile bordered with castings of leaves, beads, spindles, and other motifs for many of his works from the 1860s onward.

The frame on Harold and Mildred Colton of 1887 (fig. 73) is an elaborate version of this gilded-oak type, with a wide reverse profile. The canted frieze of gilded oak is flanked on its inner edge with cast spindles and a large laurel-leaf-and-berry design on a cushion (flattened half-round) profile and on its outer edge with a pattern of large cast eggs alternating with elongated beads. The miters of the frame corners are hidden by large cast acanthus leaves. Ernesta (Child with Nurse) of 1894 (cat. 44) is also framed in gilded oak. Its triangular profile is severely geometric, with an inner liner leading to a wide, angled, flat section and a stepped outer edge. The frame for Beaux’s portrait of Travis Cochran of 1897 (fig. 74) is of a reverse profile with a gilded liner and fluting in its interior, a shallow scoop of gilded oak at the center, and an outer edge of “Dutch ripple” design in cast composition.

The frame has a bright gilt surface overall. Similar reverse profiles with shallow outside scoops also appear on the frames for Mother and Daughter of 1898 in the photograph of the Sixty-ninth Annual Exhibition of the Pennsylvania Academy (see fig. 68) and on Gertrude and Elizabeth Henry (1898–1899; Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia).

The frame for the large, full-length portrait of Cecil Kent Drinker of 1891 (fig. 75) is composed of a wide bolection (convex) molding ornamented with naturalistic oak leaves and acorns in cast composition on a torus molding. This frame’s complicated and impressive design also incorporates corner straps and three crossed ribbons spaced over the oak leaf and acorn casts on each frame member. The cast composition is gilded over gray bole.

A large and imposing frame with a complex series of Renaissance Revival motifs appears on Beaux’s portrait of George M. Troutman of 1886 (cat. 13). The elaborate series of composition castings includes beads, spindles, and reels on the interior of the frame, an inner cove ornamented with a rich pattern of overlapping acanthus leaves, and a knull edge with large leaf spirals.

The American expatriate painter James McNeill Whistler, who designed many of his own frames, was an important and influential figure in both the English and American Aesthetic movements. Reeded frames appear frequently on many of Whistler’s works from the 1870s onward; his designs of stepped bundles of reeding were popular with late-nineteenth and early–twentieth-century artists, including Beaux. Ethel Page of 1884 (National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, D.C.) is in a reeded frame of cast composition and bright gilding. Mrs. Isaac Newton Phelps Stokes (Edith Minturn) of 1898 (cat. 59) appears in a 1902 installation photograph of the Seventy-first Annual Exhibition of the Pennsylvania Academy in the wide, reeded frame that is still with the painting today.

The frame is brightly gilded in pale gold leaf over red bole (fig. 76). The reeding appears on a wide cushion near the liner and is bordered on the outer edge with a small frieze and an astragal (bead) molding. The portrait’s long, narrow format recalls some of Whistler’s portraits, as does Beaux’s inclusion of Japanese prints in the background. The frame is labeled by its maker, George F. Of, who had a shop at 4 Clinton Place in New York in these years. The frame is surrounded by its original protective “shadow box,” an outer frame of black-stained oak that is visible in the installation photograph. Protective outer frames of this type are frequently seen on delicate frames of the period.

Frames of simple unadorned moldings also appear on some of Beaux’s paintings- for example, on the full-length double portrait Dorothea and Francesca (The Dancing Lesson) of 1899 (cat. 55). This painting is framed in a simple, narrow, gilded molding that appears to be original, owing to its appearance on the painting in an installation photograph of the Sixty-eighth Annual Exhibition of the Pennsylvania Academy in that year (see fig. 34). The molding exhibits a small concave scotia in its inner cove, a wide “thumbnail” knull edge, and a hollow outer cove. It stands in contrast to the more elaborate frames that Beaux generally favored in this period.

The Arts and Crafts Movement

At the close of the nineteenth century, the Arts and Crafts Movement brought heightened interest in individual frame design and heralded a move away from mass-produced, cast composition frames. American artists such as Hermann Dudley Murphy (1867–1945) and Charles Prendergast (1863–1948), who were themselves skilled craftsmen and carvers, began to make their own frames and to receive orders for custom work from other artists. The latter part of Beaux’s career parallels the American Arts and Crafts Movement, which produced some of its most distinctive frame designs in the first three decades of the twentieth century.

The design sources for Arts and Crafts period frames make for an eclectic blend. They include Italian, French, and Spanish frames from the fifteenth through the eighteenth centuries. Motifs were combined freely, and the precise details of early frames were sometimes given a more organic and sinuous surface treatment in interpretations that reflected Art Nouveau at the close of the nineteenth century.

The Reverend Matthew Blackburne Grier of 1892 (cat. 37) is framed in an early version of an Arts and Crafts frame that is based on Italian cassetta designs of the Renaissance. A cast design of sausage-like spindles and reels on the inner edge of the Grier frame flanks a wide, flat frieze of fine cast reeding. The frame’s outer edge, now missing, probably was composed of a small, cast Classical pattern. This simple cassetta style was popular in the 1890s as an alternative to the more traditional and fussy Barbizon-style frames with rows of cast acanthus leaf and other ornament on a large ogee (an elongated reverse or S-shaped curve) or quarter-round profile. This frame bears a label on its back from Earles’ Galleries in Philadelphia. A similar frame appears on the portrait of Mary Rodman Foxof 1892 (fig. 77), where the flat, reeded frieze is bordered by a cast pattern of oak leaves, acanthus leaves, and shells on an ogee profile on its outer edge and by a modified spindle-and-reel pattern on its inner edge.

Due to their highly individual character, picture frames designed by the renowned Beaux-Arts architect Stanford White (1853–1906) represent a distinct departure from the most popular contemporary revival styles of the period. Starting in the mid-1880s, White, a partner in the firm of McKim, Mead and White, designed frames for artists whose work he supported and whom he counted as friends, including Thomas Wilmer Dewing (1851–1938), Dwight William Tryon (1849–1925), and Abbott Handerson Thayer (1849–1921). Though White took requests for frame designs from his artist friends seriously, he viewed designing as an avocation and never charged for his designs. White’s frames inspired imitators, and some of his designs were adapted and manufactured by Arts and Crafts firms such as the Newcomb-Macklin Company of Chicago and New York (founded 1871) after his death in 1906. Thus, frames that suggest White’s designs may also appear on paintings by artists who had no known relationship with him during his lifetime. Beaux may have had an indirect connection to the architect through her close friends Richard Watson Gilder and Helena de Kay Gilder, as White had remodeled their homes in New York and on Cape Cod.

As a leading architect of the American Renaissance cultural movement, White was encyclopedic in his knowledge of Italian Renaissance and Baroque architectural motifs and could combine them with an unerring sense of harmony and proportion. Frames that White saw and collected during his European travels served as models for a number of his own designs. Some were fairly literal reproductions of antique frames, but more often White combined seemingly disparate motifs into daring yet harmonious designs. The frame for Mrs. George W. Childs Drexel (Mary Irick) of 1894(fig. 78), almost certainly a White design, displays Renaissance motifs on a broad reverse ogee profile. The profile itself finds its origin in seventeenth-century Italian frames.

This frame bears a distinctive Stanford White design trait in the form of an openwork “grille” of imbricated (overlapped like scales) fretwork mesh on its outer edge, suspended over a gilded background for a subtle effect of depth. This grille is made of gilded plaster cast over a wire armature. The upper edge of the molding near the painting bears a typical White motif in the form of a course of large, imbricated laurel leaves and berries with crossed straps at the centers, lending it an architectural feel.

The frame for Man with a Cat (fig. 79), probably inspired by White’s designs, reflects seventeenth-century Dutch and Italian sources. The Italian Baroque–style reverse profile of polished figured oak is overlaid with a series of moldings. The use of polished wood rather than gilded gesso is unusual for a White design. The frame’s inner edge bears a reeded cushion molding of a type that was used in frames designed by both Whistler and Degas. Its scooped outer cove is bordered on the outer edge of the profile by beaded moldings, including one with an outset, or crossetted, contour in the corners, which overlay the cove in a manner reminiscent of seventeenth-century Dutch frames.

Some works by Beaux from the 1890s to the 1920s were framed in distinctive interpretations of seventeenth-century Northern European “cabinet” frames, with a flat “plate” profile overlaid with crossetted corners, gadrooned interior moldings, and outlining in both wave and ripple moldings. Although the most elaborate of these frames are actually of Flemish and German origin, they are more frequently called “Dutch frames.” A black or dark brown stain allows the grain of the oak carcass to show through as a subtle textural element, as there is no gesso layer. This type of frame was also available gilded overall, unlike its dark seventeenth-century models. The black Dutch frame is a daring choice in this period, when gilded frames still predominated. Dutch-style frames in black were also used at this time on Western “nocturne” scenes by Frederic Remington (1861–1909), and polished fruitwood examples were often used by Dutch-inspired trompe l’oeil still-life painters like William Michael Harnett (1848–1892) and John F. Peto (1854–1907) from the 1880s to early 1900s.

The dark brown frame on New England Woman of 1895 (fig. 80) effectively sets off the blue and lavender tones in the white drapery, while echoing the dark notes of the table and the sitter’s hair in the painting’s otherwise high-keyed palette. The wide moldings, almost architectural in character, act as a sort of window through which we view this intimate interior scene. An installation photograph of the Sixty-fifth Annual Exhibition at the Pennsylvania Academy in 1895 shows this frame to be original to the painting.

In Sita and Sarita (cat. 41), a similar frame on a somewhat more eccentric composition echoes the color of the black cat and the sitter’s dark hair. The dark frame also allows the somber background colors to be legible. A bright gold frame would have overpowered the subtle interplay of dark tones in the upper portion of the composition and made them appear as an undifferentiated dark mass. Thus, the dark Dutch frame works equally well with both the brightly colored draperies and the dark passages of these paintings. The frame for a replica of Sita and Sarita (Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.), which Beaux painted around 1921, is identical in design to that on the original painting. The portrait Mrs. Thomas A. Scott (Anna Riddle) (cat. 51) is framed in a narrow, black, scooped molding with a gadrooned edge that recalls simpler seventeenth-century Dutch frames. An installation photograph of the painting in the Sixty-seventh Annual Exhibition at the Pennsylvania Academy in 1898 shows it in this frame.

The Rococo Revival

Concurrent with Beaux’s use of Arts and Crafts frames, many examples of Rococo Revival designs are found on her portraits at the turn of the century. Some large frames Beaux used for full-length portraits in these years are of cast composition in the period version of Rococo Revival based on Louis XV models from the eighteenth century. The early Rococo Revival of the 1830s to 1850s produced some of the heaviest and most flamboyant of nineteenth-century frames. The later revival, as seen in Beaux’s frames, was lighter in feeling, with mostly unadorned coves and foliate tendrils in low relief or reeding along the upper edge of the frame members. Some of the later frames have straight sections between the corner and center cartouches rather than the swept cyma (reverse, or “S”) curves of true Rococo design, in a sort of conflation of French Régence and Rococo styles.

Rococo Revival frames were a conservative and elegant frame choice in the late 1890s and early 1900s; the English dealer Joseph Duveen framed many Old Master paintings and English portraits, sold to great collectors such as Henry Clay Frick, in high-quality, carved, contemporary interpretations of Louis XV designs. The style was particularly well suited to vertical figural compositions, especially when these compositions depict a sitter in a Rococo Revival interior with architectural elements and furnishings that echo the sweeping curves of the frame’s profile, as in Beaux’s Mrs. Larz Anderson (1900–1901; Anderson House, The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, D.C.). The frame on the portrait of Mrs. Anderson is visible on the painting in an installation photograph of the One Hundredth Annual Exhibition of the Pennsylvania Academy in 1905.

The Rococo Revival frame on Mr. and Mrs. Anson Phelps Stokes of 1898 (cat. 58), constructed entirely of cast composition ornament on a molding of ogee profile, offers another fine example of this genre. The frame’s pierced outer rails visually lighten the great weight of the molding. Small cast flowers trail from corner and center cartouches that enclose shell designs. The gilding, over gray bole, is mostly matte throughout the frame’s surface, with burnishing reserved for a small central scotia molding. The seated, three-quarter-length portrait of Mrs. John Frederick Lewis of 1906 (fig. 81) is framed in a cast composition Rococo Revival frame with original bronze paint throughout much of its surface and burnished water-gilding over red bole on some of its moldings and on the highlights of cast motifs. Pierced cast composition cartouches with leaves and shells appear on the centers and corners of the frame.

This frame is shown on the painting in the installation photograph for the 102nd Annual Exhibition of the Pennsylvania Academy in 1907. It bears a label on its reverse from the Art Gilding Company of 1312 Filbert Street in Philadelphia. Mrs. Theodore Roosevelt and Daughter Ethel (see fig. 10) and Sarah Elizabeth Doyle (cat. 63), both of 1902, are also in Rococo Revival frames.

Beaux continued to use a variety of Arts and Crafts frame designs throughout the remainder of her career. Frames of an unusual, spare, and dramatic design appear on four paintings in this study, dated 1894 to 1897: Mrs. Clement B. Newbold (Mary Dickinson Scott) (fig. 82), Mrs. Beaureau Borie and Her Son Adolf (1896; private collection), Sally Stretch Keen (ca. 1894; cat. 43), and Mrs. Alexander Biddle (1897; Philadelphia Museum of Art). The profile consists of a narrow fillet (flat section) at the sight edge, which then angles to a wide, canted, flat cove and flattens to another wide fillet at the knull edge.

This fillet is bordered on its inner edges by rows of small egg-and-dart castings or, in the case of Mrs. Alexander Biddle, by eggs and tiny berries. The cast motifs vary slightly from frame to frame. Other small cast motifs appearing on the frames include courses of beads on the outer edges of the wide knull fillet and gadrooning or meander patterns on the back edge of the frame. Softly gleaming, lightly burnished water-gilding over gray bole embellishes the cove and knull. The austerity of the geometric profile and the fineness of the castings relieve the great weight and width of these frames, which are equally well suited to bust-length or three-quarter-length works, and lend them a modern feel. The frames’ simple profile reflects an Arts and Crafts style entirely out of step with the more florid and luxurious Rococo Revival or Renaissance Revival designs.

Many Arts and Crafts frame designs in the early twentieth century allude to Italian and Spanish Baroque models of the seventeenth century, incorporating such motifs as large, scrolled, foliate carvings in the centers and corners of the frame members separated by unadorned “reposes” (panels). In Spanish Baroque frames, the surface is frequently “parcel-gilt,” with gilded scrolls and painted reposes. Black-painted reposes were most frequently associated with Spanish frames when they were mimicked in the twentieth century. Spanish frames often provided the inspiration for productions by Boston Arts and Crafts frame makers such as Foster Brothers (founded 1875) and Hermann Dudley Murphy’s firm, Carrig-Rohane (founded 1903); such frames, in gold or in black and gold, appear on many paintings by such artists as Edmund C. Tarbell (1862–1938), William McGregor Paxton (1869–1941), and other members of the Boston School. Beaux’s move to a summer studio in Gloucester, Massachusetts, in 1905 placed her within the circle of Boston framers.

A carved frame of Spanish Baroque inspiration, with large corner and center leaf scrolls, an unusual series of overlapping shield forms on its outer edge, and a course of spindles and beads on the sight edge, surrounds Beaux’s Mrs. Richard Low Divine ( Susan Sophia Smith) (fig. 83). The frame is gilded entirely over red bole. A cipher of “Fb” on its back suggests that the frame may have been made by Foster Brothers. A frame of similar design, parcel-gilt in black, appears on the portrait of Helena de Kay Gilder (cat. 75). Another parcel-gilt frame of Spanish design—with corner scrolls, center leaf carvings, and black-painted reposes with a rippled texture—appears on Marion Reilly, Dean of Bryn Mawr College (1907–1916) (fig. 84).

This frame bears a label on its back from the frame-making firm Copley Gallery of 103 Newbury Street, Boston. An exhibition label for the 114th Annual Exhibition of the Pennsylvania Academy, filled out in Beaux’s handwriting, is also present on the reverse of this frame, indicating that it is contemporary with the portrait. Catherine (Eddy) Beveridge—Lady Primrose Portrait, painted at Gloucester in 1913, is also framed in a Spanish parcel-gilt frame with black reposes and gilded center and corner leaf carvings in low relief on a cushion profile. This frame also bears a Copley Gallery label.

The carving on the frame for Ada Louise Comstock of 1922 (fig. 85), with its abstracted, carved leaf forms on a spindle-like half-round knull edge, resembles that on the knull edge of a labeled Foster Brothers frame in the Julius Lowy collection. The Comstock frame is narrow, with the carving on the central part of the frame, whereas the Lowy frame has a wide, scooped profile with the carving on the outer knull edge.

The frame for Mrs. Addison C. Harris of 1917 (fig. 86) features a carved cushion profile with slightly curving, elongated laurel leaves, which lend it an Art Nouveau feel; the leaves emanate from central clasps on each frame member and terminate at the corners in an unusual motif of leaf-like scrolls covering small berries. The maker of this inventive frame is not known. The same design also appears on Agnes Irwin (1908; Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, Harvard University Portrait Collection, Cambridge, Massachusetts). Another similar frame design with laurel leaves surrounds the large portrait of Mrs. Stephen Merrell Clement (1910–1911; Greater Buffalo Chapter, American Red Cross, New York), painted in Gloucester.

Four half-length portraits by Beaux were framed in identical carved Arts and Crafts frames in 1912 and 1913. They appear on Clement B. Newbold (see fig. 69), Congressman Sereno Elisha Payne (1912; Committee on Ways and Means, United States House of Representatives, Washington, D.C.), John Whitfield Bunn (1913; Bank One, Springfield, Illinois), and Margaret W. Cushing (1913; The Historical Society of Old Newburyport, Massachusetts). These simple but effective frames with a lightly toned gold finish have deeply scooped coves, quarter-round sight-edge moldings, and a raised thumbnail knull edge. The hand-carved moldings and cove show the softened gouge marks and slightly irregular contours characteristic of many Arts and Crafts frames.

The frames are almost geometric in their design, without a hint of naturalistic foliate carving. Their principal distinguishing feature is a series of shallow, carved, imbricated scales that radiate from the corners of the interior cove. The cove miters themselves are covered with a striated, shell-like motif that overlaps the beginning of each row of scales. Beaux painted the portraits in several different locations, including Philadelphia, New York, and Gloucester. A bill dated May 17, 1912, from the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts to Beaux for “express charges on frame for Mr. Newbold’s Portrait from the Copley Gallery, Boston,” indicates that Copley’s made these frames. The existence of this series of four identically framed works executed within such a narrow time frame is perhaps the best indication of Beaux’s taste in framing at a particular moment, as it is certainly no coincidence that they all bear the same frames, and no consensus to use identical frames can have been arranged by so diverse a group of sitters.

A simple molded frame appears on Beaux’s portrait of George Dudley Seymour, The Green Cloak (fig. 87), one of the latest paintings studied here. This modernist frame with a series of streamlined moldings on a narrow scooped profile expresses an Art Deco sensibility with its rounded corners. Although it may seem an unusual choice for Beaux, the presence of paint on the inner edges of the frame rabbet that matches the edges of the painting, and a label on its back for the 121st Annual Exhibition of the Pennsylvania Academy in 1926, indicate that this is the picture’s original frame. The frame is labeled by the maker, V. Grieve Company of New York and London.

Canaletto Frames Some of Beaux’s later portraits are framed in distinctive moldings of medium weight with a quarter-round or cushion profile embellished with foliate carvings in low relief in the centers and corners alternating with unadorned reposes. These frames are based on Louis XIII models of the early seventeenth century and on British Baroque interpretations of these designs from the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries—the so-called “Lely frames,” named after the English portrait painter Sir Peter Lely (1618–1680), on whose works they so often appear. For similar reasons, Venetian Rococo frames of the early eighteenth century are often called “Canaletto frames” after the Italian painter Canaletto (1697–1768). These frames also contain carved foliate-and-leaf corner and center panels in low relief between unadorned reposes on an ogee profile. Many Arts and Crafts frame makers designed frames that alternate low-relief foliate-and-leaf carving with reposes.

The carved and gilded frame on A Lady in Black (Mrs. Alfred du Pont) (fig. 88) is of this type. It is similar to a frame in the Lowy collection identified as being made by the Boston firm of Foster Brothers, except for its larger size and lack of ornament on its sight edge. The Lowy frame has a leaf design on its sight edge. Both frames share similar foliate-and-leaf carving in low relief, separated by reposes on a cushion molding. These frames also resemble a labeled Foster Brothers frame illustrated in The Art of the Frame. The designs recall eighteenth-century Venetian Baroque frames. Canaletto frames also appear on the three-quarter-length portrait Caroline B. Hazard (1908; Wellesley College, Massachusetts) and on Mrs. Marcel Kahle (1925–1926; Collection of Lois B. Weigl).

The frame for the large double portrait Portraits in Summer (Mr. and Mrs. Henry Sandwith Drinker) (fig. 89) is a variant on a Canaletto frame, with plain, centered, recessed panels following the profile of adjacent unadorned surfaces on a narrow molding of ogee profile. The date “1911” is carved into the bottom center, presumably to commemorate the couple’s wedding date. The frame has a dark, bronze-leaf finish over red bole.

Glazed Paintings

Despite our modern preference for unglazed oil paintings, it is not unusual to see paintings by Beaux in frames that retain their original picture glass. Glass afforded paintings a modicum of protection at a time of dirty gaslights and coal heat and when packing and shipping procedures were far from ideal. Pasting paper to the surface of the glass while the painting was in transit prevented jagged pieces of glass from piercing the canvas in the event of breakage. Sometimes the sheets of glass were sent along with the framed painting in separate packaging, to be reassembled after delivery.

Photographs of paintings installed in the annual exhibitions of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts show many examples of paintings by Beaux and her contemporaries with glazed frames. A lender shipping one of Beaux’s paintings to an Academy annual asked the institution’s managing director, Harrison Morris, for advice on the subject of glazing: “I do not wish to make any suggestions as to sending without glass and I suppose Miss Beaux thinks that it is better covered. Do you know?” In a letter of 1895 from Beaux to Morris, she chides him about replacing a sheet of cracked glass on one of her portraits in an annual exhibition. She wanted it replaced as soon as possible and reminded Morris that “Haseltine [Charles Haseltine’s Galleries, Philadelphia] is always ready to do a thing of that kind at a moment’s notice.”

In another letter to Morris, written in 1911, Beaux discusses sending a glazed painting to an annual. Beaux wrote from Gloucester in 1930 to instruct the Academy’s secretary to send her well-traveled and widely exhibited New England Woman (see fig. 80) for exhibition with glazing: “The picture had a glass which is a very important consideration—If the glass is now covering it—as I hope—(for protection) I trust it may be shipped with the picture or separately—as this is the only safe way.”

The glass was held in place in the frame by removable liners. Some glazing was set between the liner and the outer part of the frame, thereby covering the liner as an integral part of the frame construction. Examples of Beaux paintings in this study whose frames retain what appear to be their original glazing include Sally Stretch Keen (cat. 43), Mrs. George W. Childs Drexel (Mary Irick) (cat. 42, fig. 78), Travis Cochran (see fig. 74), Mrs. Isaac Newton Phelps Stokes (see fig. 76), Catherine (Eddy) Beveridge—Lady Primrose Portrait, and Marion Reilly (see fig. 84).

A Taste for the Antique

Beaux may have developed a taste for antique frames late in her career, perhaps inspired by the example of Sargent and others. Three Beaux paintings in this study are framed in what appear to be period seventeenth-century Italian Baroque examples. The asymmetrical placement of what were once centered cartouches and evenly spaced reposes reveals that these antique frames have been cut down to fit Beaux’s paintings. A regilded Italian Baroque frame with acanthus-leaf carving appears on The Portent (ca. 1914; Art and Archaeology Collection, Bryn Mawr College, Pennsylvania). A black and dark-gold parcel-gilt bolection frame of probable Italian Baroque origin, with carved leaf-spiral patterns alternating with reposes, houses Ernesta (1914; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York). The painting appears in this frame in an installation photograph of the gallery of American paintings at the Metropolitan Museum of Art from July 1918.

Another Italian Baroque frame with a carved spiral-leaf design on a bolection profile appears on Flora Whitney (fig. 90). A variant on Beaux’s use of antique frames appears in a large reproduction frame on her portrait Mrs. Elizabeth M. Howe (1903; private collection), in which the vigorously carved design on a wide profile also recalls Italian Baroque design, but the machined marks on the back of the wood carcass reveal its modern manufacture (fig. 91).

Beaux’s paintings appear in a wide variety of distinctive, high-quality frames at all points in her career; their changes in design parallel the development of her aesthetic taste. If we consider only those frames that appear on her paintings in the installation photographs of the annual exhibitions at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, we would have to conclude that Beaux customarily selected stylish frames for her works. The study of other frames that appear to be original to her pictures further suggests that she chose the style of a frame based partly on the work’s size and subject and partly on the latest design trends. We are fortunate to have so many of Beaux’s paintings in their original frames to document her changing taste and to reveal the care she took in presenting her art to the public.

In addition to those acknowledged in the Notes, I would like to thank the following people and institutions, whose assistance with photography and with curatorial and archival information has been invaluable: Cheryl Leibold, Archivist, Barbara Katus, Rights and Reproductions Manager, Marissa Diamond, Digital Photography Intern, and Gale Rawson, Registrar, at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts; Carrie Rebora Barratt, Associate Curator of American Paintings and Sculpture, The Metropolitan Museum of Art; Alan Francisco, Head Registrar, Vivian Djen, Library Assistant, and Kerry Kathleen Folan, Manager, Rights and Reproductions, National Museum of Women in the Arts; Aimee L. Marshall, Manager of Rights Licensing, Art Institute of Chicago; Jeff Boyer, Conservation Technical Assistant, Toledo Museum of Art; Latishia Allen, Registrar’s Assistant, Smith College Museum of Art; Jennifer Seeds, Assistant Registrar, Columbus Museum of Art; Diane M. Hart, Museum Registrar, and Rachel U. Tassone, Manager of Collections Information, Williams College Museum of Art; Carol W. Campbell, The Constance A. Jones Curator, and Tamara Johnston, Registrar, The College’s Collections, Bryn Mawr College; Susan Erony, Associate Curator for Exhibitions, Cape Ann Historical Society; Catherine Riedel, Director of Marketing and Public Relations, Skinner, Inc.; and photographer Rick Echelmeyer of Thornton, Pennsylvania.

I would also like to especially thank my colleague Sylvia Yount, Margaret and Terry Stent Curator of American Art at the High Museum of Art, for her unflagging guidance and assistance with the content of the essay, its editing, and its innumerable production details. I also thank the High Museum’s Akela Reason and Heather Medlock for their assistance. I also give special thanks to Eli Wilner & Company, Gallery Director at Eli Wilner & Company, who kindly shared her expertise and research materials on Beaux frames. I gratefully acknowledge Eli Wilner & Company for their generous funding of photography for this essay.

1 Eastlake, Hints on Household Taste, p. 41.

2 Simon, Art of the Picture Frame, pp. 183, 185.

3 See Donald C. Peirce, Art and Enterprise, pp. 103–104, 208–209.

4 Thanks to Randi Jean Greenberg, former Collections Manager, National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, D.C., for allowing me to examine these paintings.

5 Correspondence with Pat McCormick, Archivist, Butler Institute of American Art, Youngstown, Ohio, February, 2004.

6 Thanks to Michael Stone, Frame Conservator, and Kathleen A. Foster, the Robert McNeil Jr. Curator of American Art at the Philadelphia Museum of Art,

for allowing me to examine Beaux painting and frames in their collection.

7 Thanks to Kevin Sharp, Director of Visual Arts, Cedarhurst Center for the Arts, Mount Vernon, Illinois, for sharing a photograph of this frame.

8 Randi Jean Greenberg, National Museum of Women in the Arts.

9 Katlan, American Artists’ Suppliers Directory, p. 192.

10 Correspondence with Sarah E. Kelly, Henry and Gilda Buchbinder Family Assistant Curator of American Art, Art Institute of Chicago, January 2004.

11 On Stanford White’s frame designs, see, for example, Nina Gray, “Within Gilded Borders: The Frames of Stanford White”, in Wilner,

The Gilded Edge, pp. 82–103, and Eli Wilner & Company, “Early Twentieth-Century American Frames:

The Arts and Crafts Period,”.

12 Nina Gray notes the earliest documented use of a Stanford White design by Newcomb-Macklin in 1912. “Within Gilded Borders,” p. 102.

Thanks to Sylvia Yount for pointing out the Gilder connection to me.

13 Thanks to Lynn French, Director and Children’s Librarian of the Sally Stretch Keen Memorial Library, Vincentown, New Jersey,

for allowing me to examine this painting.

14 Betsy Anderson, Collections Curatorial Coordinator, Smithsonian American Art Museum, kindly gave me information about the Beaux paintings

and frames in their collection in March 2004. Thanks to Eli Wilner & Company for bringing this frame to my attention as a possible White design.

15 Correspondence with Dominique Lobstein, Chargés d’études documentaires, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, March 2004. Thanks to Mr. Lobstein

for providing a photograph of this frame.

16 Thanks to Dare Hartwell, Conservator, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., for sharing extensive information on this frame.

17 Thanks to the Sally Stretch Keen Memorial Library for allowing me to examine this painting.

18 Simon, Art of the Picture Frame, p. 24.

19 Correspondence with Emily L. Schulz, Curator of Collections, Anderson House, The Society of the Cincinnati, Washington, D.C., February 2004.

20 Correspondence with Patricia Junker, former Curator of Paintings and Sculpture, Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth, Texas, January 2004.

21 Mark Cole, former Curator of American Art, Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio, noted this interesting cipher; thanks to Eli Wilner & Company

for bringing this frame to my attention.

22 Thanks to Carol W. Campbell, Constance A. Jones Curator, and Tamara Johnston, Registrar of the College’s Collections,

Bryn Mawr College, Pennsylvania, for allowing me to examine these works and arranging for photography.

23 Thanks to David Miller, Senior Conservator of Paintings, Indianapolis Museum of Art, for examining this frame from the museum’s collection on my behalf.

24 Correspondence with David Dempsey, Associate Director for Museum Services, and Michael Goodison, Archivist and Editor,

Smith College Museum of Art, Northampton, Massachusetts, February 2004; Julius Lowy, 20th Century American Frames, p. 8.

25 Correspondence with David Miller, Indianapolis Museum of Art, February 2004.

26 Tappert, Cecilia Beaux, p. 106.

27 Thanks to Eli Wilner & Company for bringing this to my attention.

28 Tappert, Cecilia Beaux, pp. 116, 118, 122, 120.

29 Beaux Papers, PAFA.

30 Thanks to Dawn Rogala, former conservation intern at the Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, Connecticut, for sharing her examination report

on this painting and frame.

31 Mitchell and Roberts, A History of European Picture Frames, p. 31.

32 Julius Lowy, 20th Century American Frames, p. 8.

33 Smeaton, Art of the Frame, p. 11.

34 Correspondence with Kathleen Mrachek, Research Assistant for Paintings, Art of the Americas, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, January 2004.

Thanks to the museum’s frame conservator, Andrew Haines, for examining this frame on my behalf.

35 William Amory to Harrison Morris, February 5, 1904, Beaux Papers, PAFA.

36 Beaux to Morris, December 29, 1895, Beaux Papers, PAFA.

37 Beaux to Morris, 1911, Beaux Papers, PAFA.

38 Beaux to Mr. Myers, October 26, 1930, registrar’s files, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.

Thanks to Barbara Katus, Rights and Reproductions Manager for the Academy, for bringing this to my attention.

39 Correspondence with David Miller, Indianapolis Museum of Art, February 2004.

40 Vintage photograph, July 1918, reproduced in Wilner, The Gilded Edge, p. 175.

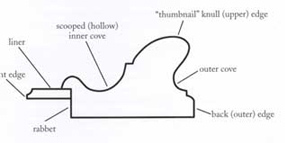

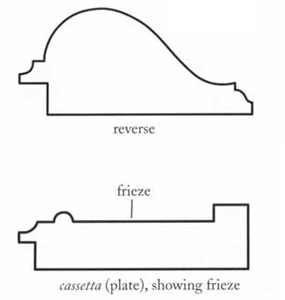

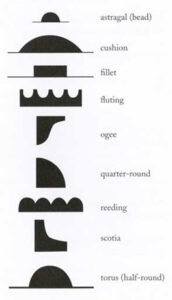

41 Thanks to Katharine Alling for information on this frame and for its photography.Bole surface for burnishing. They are most often red, yellow, or gray, and add color to the overlying thin metal leaf. Bolection A type of reverse profile frame with large convex molding on its inner edge that slopes away to its outer edges. Burnishing The rubbing of a smooth hard stone on metal leaf to create a brilliant, mirror like surface. Cartouche Projecting, scroll-like ornaments, especially those found at the corners and centers of Lous XIV, Regence, and Louis XV frames; cartouches often enclose shells, flower, or other motifs. Composition Putty made of animal-skin glue, linseed oil, chalk, and rosin. Composition, or “compo,” is pressed into moulds and cast into decorative motifs to ornament frames. Cyma Curve A line that is partly convex and partly concave. Gesso A white coating of animal-skin glue and chalk used to coat wood and castings to provide a smooth ground for gilding or painting. Imbrication Overlapping like scales. Reposes Unornamented panels adjacent to carved or cast motifs. Swept Edges Curved contours in the upper edges, or rails, of a rococo frame. Frame Nomenclature – Illustrations by the author

Parts of a frame

Moldings

Profiles

Ornaments