European Antecedents to American Frame Design

by Eli Wilner & Company Period Frames, NYC Copyright © September 1994

The source of American frame design is a rich and multi-layered terrain. Eighteenth Century American frames bear a close resemblance to their English counterparts. Indeed, most were made by European craftsmen, or at least based on English pattern books.

London and England were viewed as “home” and English decorative styles revered. An aesthetic shift came in the wake of the revolutionary war, however, when America asserted an independent new identity. A uniquely American aesthetic then began to emerge.

However, the influences of Europe are clear throughout American frame design and reflect much of the cultural context from which they were born. English architect Robert Adam’s elegant Neo-classical designs were the genesis of what we call Federal designs here in America: urns, swags and classical forms all appear on American frames of this period.

While the revolutionary war was going on in America, a revolution in design in Europe was taking place. The classical style (re-discovered by the excavations of Herculaneum and Pompeii) inspired a style based on a smaller, more domestic scale, in contrast to the Eighteenth century style modeled on large grand temples.

The Crystal Palace exhibition in London of 1851 was another source for the sharing of designs. Many frame designs on the English paintings of this period have similar counterparts in America. One frame, with an outer band of twigs and an inner cove embellished with a Moorish pattern, can be found on several pre-Raphaelite paintings in the Tate Gallery. This style is also found on Mountain Scenery by Thomas Cole in the collection of the New-York Historical Society (Figure 1).

One of the French influences on American frames can be found in the fluted cove frame frequently seen on Hudson River landscape paintings, based on French Neo-classical design. It has been made in countless renditions with only slight variations, such as the outer design element or the kind of leaf placed at the inner corners (Figure 2).

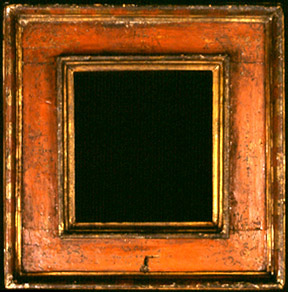

There was an incredible cosmopolitanism in America after the Civil War, when journeys to other countries were motivated by the desire to assimilate the best the world had to offer. Paris had become the place for those interested in art. Just as there were American painters who were influenced by the French Barbizon school of artists, there were American frames crafted in close detail to the frame style most often seen on French Barbizon paintings: a floral composition based on earlier Louis XIII frames (Figure 3).

James McNeill Whistler’s use of reeded molding and the application of gold leaf onto the wood surface without the gesso layer was a choice directly attributable to his artist friend Dante Gabriel Rosetti and the English pre-Raphaelite artists who were themselves experimenting with new frame designs. Architect Stanford White was a great fan of Italian Renaissance architecture and design and popularized the use of the tabernacle form so widely used in Italy centuries before (Figures 4 and 5).

Seventeenth century Dutch style frames enjoyed a revival at the turn of the Nineteenth to the Twentieth century and are often seen on art works of this period. The crossetted corner on Dutch frames can be found in frames designed by both White and Foster Brothers of Boston. Foster Brothers used this form on frames they designed for William MacGregor Paxton and Edmund Tarbell, who were themselves studying the works of the Seventeenth century Dutch artist Vermeer (Figures 6 and 7).

Artist and framemaker Hermann Dudley Murphy revolutionized early Twentieth century frame design with his turn away from composition ornament and Nineteenth century frame profiles, instead introducing his frame design of a broad flat panel and simple carved corner elements. This composition was inspired by the Fifteenth and Sixteenth century cassetta frames he had seen during his travels in Italy (Figures 8 and 9).

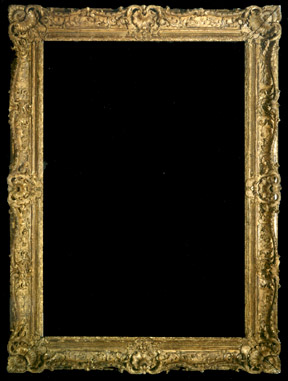

And certainly no one has escaped seeing the infinite number of variations on Louis XV Rococo frames on Impressionist art. Though widely disparate from the original vision of the artists themselves, and clearly inappropriate to the Impressionist aesthetic as we view it in retrospect, these Rococo frames have been placed on Impressionist paintings as a standard practice on both sides of the Atlantic for nearly one hundred years (Figure 10).

The next time you visit a museum, take some time to walk through the European collections. Then visit the American paintings. As you compare not only the paintings, but their frames as well, you will gain insights into the long history of shared ideas that is at the very heart of the study of art.