The Arts and Crafts Period

by Eli Wilner & Company Period Frames, NYC Copyright © October 1991

The change in the design and construction techniques of picture frames in the late 19th century echoed the larger cultural trends in evidence at the turn of the century. When a frame from the early years of the 20th century is contrasted with its 19th century counterpart, several distinct differences are immediately apparent; first the applied composition ornament that had been so completely predominant is absent, second the profile that had been deep and heavy is more shallow and flattened out, often sloping away from the picture plane, and third many more tonalities of the gilded surface are apparent.

The trend away from complex profiles with applied composition ornament was in many respects a reaction to the mass production and industrialization that had so permeated late 19th century business and industry. Many felt that efficiency had been valued over artistry and supported a return to earlier methods of craftsmanship, such as hand carving. In another way, the change in frame styles also echoed the change in painting styles. The new Impressionist and Post-Impressionist canvases, with their brushwork and colorful palettes, needed to be enclosed by something new, and many artists, attuned to the importance of sensitive framing, designed and/or crafted new frames which they felt were more sympathetic to their works.

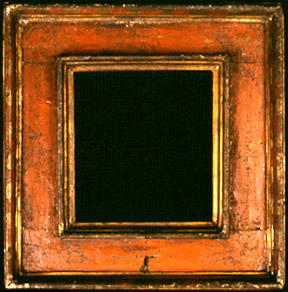

One such artist was the Boston painter Hermann Dudley Murphy, who taught himself the skills of carving and gilding and crafted beautiful frames, signing and dating each frame on the back. One of Murphy’s most profound contributions was his re-interpretation of the Venetian casetta frame (Figure 1). The Italian predecessor, with its broad flat center panel and sgrafitto corner decorations, was transformed by Murphy into a gilded surround with carved corner decorations. This style became the favorite of many other artists such as Willard Metcalf and Childe Hassam, who modified the original design for their own uses. Today, countless variations made by a variety of framemakers appear on paintings of the period. (Figure 2)

Other innovators influenced frame design as well. Architect Stanford White introduced elegant frame designs with shallow profiles that sloped back and away from the picture plane and often incorporated architectural elements (Figure 3). Foster Brothers of Boston carved frames that incorporated synthesized elements of early Dutch frames such as crosetted corners for Boston School artists Edmund Tarbell and William MacGregor Paxton who were influenced by the Dutch artist, Vermeer (Figure 4). The Newcomb-Macklin Company of New York and Chicago crafted many beautifully carved and gilded frames during this period, and both Frederick Harer (Bucks County, Pennsylvania) and Charles Prendergast (Boston) experimented with incising into the gesso surfaces of their frames, creating unique and delicate surface patterns (Figure 5).

Almost all these innovators paid special attention to the subtleties of the gilding process. Many experimented with the many possible tonalities of gold and also with white gold and silver leaf. Peyton Boswell stated in an article for House and Garden in 1929, “The best frames are covered with leaf gold, which is afterwards, by means of chemicals, toned to any hue that harmonizes with the picture. The use of gold provides the ‘highlights’ that are necessary in a frame. It is remarkable what color effects… can be produced.”

Boswell best summed up feelings of many artists and framemakers of the Arts and Grafts period when he stated, “… when we come to Impressionist pictures and works by the modern colorists, there is nothing in the whole past of framemaking that is appropriate.” Indeed, this search for more complementary frame designs has left us with many fine examples of the power and subtlety present in these beautifully crafted picture frames.