Frames in Context: Four Men and Their Vision

by Eli Wilner & Company Period Frames, NYC

Reproductions or Exact Replica Frames?

Learning to see the Difference

To fully understand the profound impact of the new picture framing styles advocated by four artists, James Abbott McNeill Whistler, Frederic Edwin Church, Stanford White and Hermann Dudley Murphy, it is illuminating to view the cultural and aesthetic contexts from which their art and ideas emerged. The shift in aesthetic ideals in the mid-l9th century redefined art in all its forms, extending even to the conceptual intermediary, the picture frame.

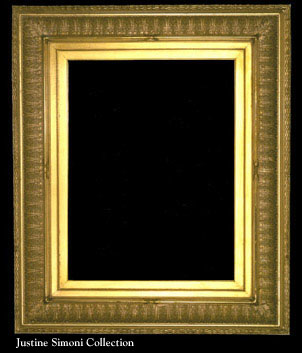

Through the ages, the frame has embodied a unique combination of practical function and artistic statement. The frame surrounds the art that is an illusionistic world into which one can venture, both representing reality and removing us from it. The predominance of the gilded frame in particular allows for a reflective halo effect which forms a boundary, as art critic and writer Percy Fitzgerald phrased it in 1886, “between the vulgar surrounding world and the sort of spiritual life of Art.”

In performing its function, the frame most often does not call attention to itself. Indeed, it is likely that if one were to conjure images of the paintings he knows best, he would find that he cannot recall the frames in which they rest. This is particularly true when the marriage of painting and frame is a sensitive and successful one; as John Russell, art critic for the New York Times so aptly notes, “There are frames that a great painting seeks to sink into with rapture and relief. And there are others that provoke in the painting an almost palpable cry of pain. (New York Times, June 24, 1990.)

The English reform movement, in evidence as early as the 1830s, was a strong response to the social transformations being wrought by the Industrial Revolution. Central to the debate was John Ruskin, an art critic and writer who brought a religious zeal to his beliefs about the necessity of being true to nature, the sanctity of the natural universe and the importance of art in a healthy society. Even within the reform movement, however, there were different perspectives and voices, and many espoused the need for a more central role of art in everyday life without subscribing specifically to Ruskin’s dogmatism and rigidly purist views. Christopher Dresser, a trained botanist, while advocating the use of natural forms as the basis for ornament, did not condemn industrialism and machine production as did Ruskin. Owen Jones, an architect by training, exerted enormous influence on 19th-century design when he published The Grammar of Ornament in 1856, a compendium of almost 2,400 conventionalized designs from many historical periods and cultures, as well as from nature. A second smaller volume, issued in 1864, introduced Western artists to non-Western patterns, especially Islamic and Moorish designs, demonstrating the beauty inherent in abstract and geometric surface ornament.

It was in this environment that the American expatriate, James McNeill Whistler, while living and working in England, first designed frames. These harmonized more effectively with his paintings and their provocative and innovative use of form and color, a style which contrasted with the prevailing style of narrative painting. A close friend of many of the Pre-Raphaelite painters who were themselves exploring alternative frame designs, Whistler enjoyed a particularly strong association with Dante Gabriel Rosetti. Whistler’s design for the frame on Caprice in Purple and Gold: The Golden Screen exhibits several stylistic similarities to Rossetti’s earlier frames, such as broad flat surfaces and the use of decorative rondels situated around the panel. Whistler, however, always created his own unique designs and displayed a great talent for employing numerous historical sources for his own creative use; his collection of Oriental ceramics and his study of Japanese prints greatly informed the compositions of both paintings and frames. Designs from Owen Jones’ The Grammar of Ornament appear on several of his frames.

Across the Atlantic in New York in the late 1860s, the successful Hudson River landscape painter, Frederic E. Church, was struggling with the waning popularity of his style of naturalistic landscape painting. Franklin Kelly explains that painters incorporating the human figure such as Winslow Homer and James McNeill Whistler were gaining favor, and the more intimate landscapes of artists like George Inness were more suited to the mood of post-Civil War America.” In 1865, after a brief trip to Jamaica, Church, who had often traveled to remote locations for material for his paintings, planned a trip to the Near East. To prepare for the trip, he read extensively from such widely varied sources as travel literature, Biblical narratives, history and science texts, and Oriental romance novels. In October of 1867, he departed for Europe.

Church stopped briefly in London in 1867, before his travels throughout the Near East, and then again prior to his return in the summer of 1869. It is certain that Church was much interested in the prevailing artistic atmosphere of England at the time; he had long maintained ties with England, having been an early disciple of John Ruskin.

Church’s travels provided him with innumerable sources of inspiration. The rich designs of Persian architecture and even the palettes of color manifested in the Near Eastern geography and architecture would inform both the complex and unique picture frames which he designed to enclose the paintings born of his recent travels and his later creation of his home, Olana, in Hudson, New York. In 1870, Whistler and Church began independently to create interiors. It was also the year that the 16-year-old Stanford White began his architectural training in the offices of Henry H. Richardson.

Following his return from the Near East, Church set about the design and building of his home, while continuing to paint the landscapes which so intrigued him. Thoroughly enamored with the Moorish shapes and patterns, Church used his new-found knowledge to best advantage in frame-making. Though still characteristic of heavy 19th-century designs, Church’s frames now often employed a broader, more shallow shape.

In El Khasni, Petra, 1874, which Church painted for the sitting room of Olana, the designs in the frame are part of a much larger decorative scheme of stenciling, carved wood surfaces, stonework and decorative objects seen throughout the room. The pink marble used in the fireplace even echoes the coral shades in the painting displayed above it. (Figure 1)

While Church was creating his Near Eastern paintings and frames, Whistler continued to design frames for his pictures.

The frames he created during this period departed from the frames he had created for his Oriental series, though they still employed elements of design used earlier by the Pre-Raphaelites. Notable among these devices was the use of reeded molding, as seen in Rosetti’s Annunciation (1861). The reeded molding, so named because it resembles a bundle of reeds, was used in varying combinations of both size and quantity.

The clean, undecorated lines were a perfect complement to Whistler’s tonalist compositions.

The use of reeded molding was often combined with another decorative device of the Pre-Raphaelites that involved applying the gold leaf directly to the wood surface without the usual ground layer of gesso; in this way the subtle grain of the wood showed through and allowed for a softer value of gold than the highly burnished and reflective surfaces of conventional water gilding. No stranger to the nuances of color, Whistler would in fact choose specific compositions of gold leaf that were more green or red than the standard yellow gold. (Figure 2)

Among Whistler’s works on interiors, the Peacock Room of 1876-77’s most notable. The architect Thomas Jeckyll had been hired by shipping baron Frederick Richards Leyland to remodel his dining room so that he could display his extensive collection of blue and white Oriental porcelain and La Princesse du Pays de Ia Porcelaine, painted 12 years earlier by Whistler. Jekyll drew upon many of the same decorative sources as Whistler, as seen n the incised designs in Jeckyll’s walnut shelving which are found in Jones’ The Grammar of Ornament, as well as the use of reeded moldings in the ceiling reminiscent of those used by the Pre-Raphaelites.

Whistler’s artistic choices eventually over-shadowed both Jeckyll’s work and his associations with the Peacock Room; what was originally a dark Dutch-style room with deep brown leather wall hangings and natural walnut shelves was transformed by Whistler into a room of multilayered painted surfaces that created a shimmering blue-green surface accented by highlights of gold in both the peacocks on the walls and Jeckyll’s walnut shelving, now gilded. Whistler gave the room the official title, Harmony in Blue and Gold.

For Stanford White, the mid to late 1870s were enormously formative; White’s early apprenticeship to H. H. Richardson which included work on the monumental Trinity Church in Boston, his visit to the pivotal Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia and his first trip to Europe all contributed to the rich artistic expression in the years to follow. An interesting coincidence of 1877 was that the consecration of Trinity Church took place on the same day, February 9th, that Whistler held his reception for the press at the Peacock Room.

In his personal life, White’s closest friends and associates were artists active in the aesthetic redefinition so much in the forefront at the time. His participation in the Tile Club, formed in 1877, provided him with an unconventional atmosphere and aligned him with artists who lived the artistic directive of their day to make “art for art’s sake.” Augustus Saint-Gaudens, William Merritt Chase, J. Alden Weir, John Twachtman and Edwin Austin Abbey, to name a few, remained close to White throughout his life.

Upon White’s return from his first European sojourn in 1880, the partnership of McKim, Mead and White was formed. The hallmark of White’s career is not just his contribution to architecture, but also his unique and inspired interior decorative schemes. Time and again throughout his career, his attention to the use of materials and decorative elements displayed a unique talent. His sensuous combination of wood carving, glazed tiles, stained glass, marble and brass earned him praise early in his career and throughout his lifetime. It is not surprising, then, to see the refined and complex vision White brought to his design of picture frames an obvious adjunct to his work as an architect and his close friendships with numerous artists. His earliest known frame designs, dating from about 1884, were those created to surround the women in his life both an oil by Thomas Wilmer Dewing and a marble relief by Saint-Gaudens were portraits of his wife Bessie; another was a portrait of his mother by Abbott Thayer.

By the 1890s, his frame designs were well-known. The styles were of two types: the tabernacle-style frame like that on the marble relief of Bessie, and a simpler profile frame seen frequently on the works of Dewing and Dwight Tryon. The latter profile is important in that it was broad, nearly flat, and it sloped away from the picture surface in decided contrast to the more conventional profiles of earlier 19th-century frames which were deep and which sloped down toward the picture surface. Though White did not make the frames himself, he did create meticulous drawings of their ornamentation and closely supervised their execution by chosen craftsmen. (Figure 3)

By the 1890s, his frame designs were well-known. The styles were of two types: the tabernacle-style frame like that on the marble relief of Bessie, and a simpler profile frame seen frequently on the works of Dewing and Dwight Tryon. The latter profile is important in that it was broad, nearly flat, and it sloped away from the picture surface in decided contrast to the more conventional profiles of earlier 19th-century frames which were deep and which sloped down toward the picture surface. Though White did not make the frames himself, he did create meticulous drawings of their ornamentation and closely supervised their execution by chosen craftsmen. (Figure 3)

David C. Huntington, a professor of art history, aptly described White’s frame on Dewing’s Summer in the following way: “Intimate in its details, reticent in its features, this frame, itself an original work of art, is the perfect surround for a scene too fragile for any but the most sympathetic of eyes.” In this frame style, White designed several surface treatments, all of them at once rich and complex, refined and restrained. In White’s tabernacle frames, many of which appear on Thayer’s angel pictures, we see his appreciation for the Italian Renaissance features well-known in many of his architectural designs; they are a perfect complement to the classical depiction of Thayer’s young women. In the early 1880s, while White was designing his first frames in New York, the young student Hermann Dudley Murphy was studying art at the Boston Museum School. Just as White created frames for artworks reflecting the late 19th-century shift to classicism and idealized images, Murphy created frames for the Impressionist and Post-Impressionist works that prevailed at the turn of the century.

The influence of Whistler on the paintings of Murphy, noted for their color harmonies and refined compositions, is no less evident than his influence on Murphy’s ideals concerning the importance of the picture frame. At the time of Murphy’s studies in Paris under Jean-Paul Laurens and J. J. Benjamin-Constant at the Acad mie Julian, Whistler was active in Paris, and his studio was a gathering place for young Americans.

Murphy returned to the United States in 1897, the year that a group of artists, noted in part for their Impressionist works seceded from the Society of American Artists to form “the Ten.” Upon his return Murphy was unable to afford the fine frames he felt his work so deserved and went about gathering the tools and skills necessary to create them himself. Already by the following year, in the reviews of his work, Murphy was credited with beauty and skillfulness in the frames he created to surround his works. By 1903, Murphy had built himself a home and studio in Winchester, Massachusetts, that he named Carrig Rohane, Celtic for “red cliff” – a reference to his Celtic heritage, yet another kindred connection to Whistler, also a Celt. In that same year, Murphy invited Charles Prendergast, the brother of Maurice, to join him in the Carrig-Rohane frame shop. Though Murphy’s designs enjoy many historical influences, one of the most significant is that of the 16th and 17th-century Venetian cassetta frame. The cassetta, with its broad flat center panel and raised inner and outer edges, became a favored choice for Murphy. The sgraffito decoration at the corners of the center panel of the Venetian prototype became a carved design situated on the outer section of Murphy’s creation.

The flat, unadorned frame was the perfect foil to the Impressionist paintings, which employed such new palettes of color and new styles of brushwork. With Boston as a leading center of art in the United States, Murphy’s new frame designs were quick to gain favor and recognition; many would inspire variants adapted to the specific tastes of other artists who favored the use of this new frame style. (Figure 4)

The flat profile would show to best advantage the subtleties of the gilding process acknowledged years earlier by Whistler. Many new shades of gilding were used on the frames to best harmonize with the canvases they surrounded. The kinship of Whistler and Murphy is further evident in Murphy’s use of a cipher, as Whistler used his butterfly on paintings and frames alike. Murphy appears to be the first American artist to specifically acknowledge the artistry inherent in his frames – each is signed and dated on the reverse. In addition to frames for his own works, Murphy created frames for some of the leading artists of his day, such as Edmund C. Tarbell, William MacGregor Paxton and Frank W. Benson, and it is fitting to see Murphy as the leader of a veritable revolution in the design of American frames that would show itself for decades to come.

It is interesting to ponder the “cross-pollination” in the works of all four men. We know that Church was a Ruskinian – his allegiance to that of the noble and the sacred in nature – and that he would have been all too aware of Whistler’s iconoclastic views both before and during his Near Eastern travels. We know, too, that in 1895 Stanford White spent an evening with Whistler in Paris and saw the Peacock Room in London, later writing the artist that he hoped to bring it to the United States. And, finally, we know of Whistler’s impact upon the young student Murphy, who would later open his own Carrig-Rohane frame shop in Boston in 1903, the same year that Whistler was memorialized in the Boston exhibition of his work. It is a fitting tribute that these four men can now be acknowledged for their enduring influence on the way we see art.