Frame's the Game

Reprinted with permission Forbes, October 9, 1995 By Ann E. Berman .

Some people have become so enamored of picture frames that they throw away the pictures.

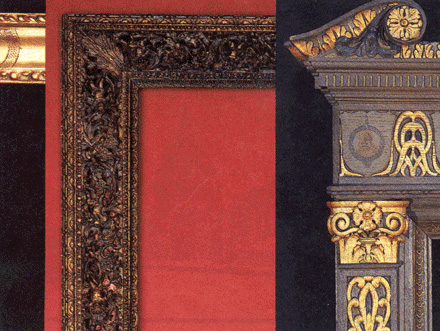

“THE FRAME IN AMERICA, 1860-1960,” at the gallery at the Federal Reserve Board in Washington, D.C. (January-March 1995), was the most popular exhibition in its 20-year history. Just frames? No pictures? America is catching on to these long-neglected objects, which have been hot in Europe for decades. London frame dealers Arnold Wiggins & Sons Ltd. recently paid a record $54,000 for an 18th-century English Palladian frame at auction, and private sales have exceeded $100,000. Michael Gregory, the managing director of Arnold Wiggins, notes: “Period frames have a history, a patina that eludes modern gilders. They are full of subtleties, they are art objects.”

You’d expect Gregory to say that. But in a way, history is on his side. Since the 15th century – when the form as we know it first appeared – frames have often cost more than what was in them. Framemaking commanded the same respect as cabinetmaking or architecture and mirrored the prevailing decorative and architectural styles.

Italian artisans carved the crisp flourishes and applied the subtle gilding that set off Renaissance masterpieces. It took real skill to fashion the swirling curves of the French Baroque, the deceptively simple black wood moldings preferred by 17th-century Dutch burghers, the Moorish designs of Spain or elegant English Palladian frames. In the 19th century, “composition” frames – which were made of a kind of plaster – caught on, but hand-carved frames continued to be made. In this country turn-of-the-century designers like Stanford White, Arthur and Lucia Mathews and Charles Prendergast created some of the most beautiful American frames ever made.

By 1950 hand carving was too expensive and period frames went out of style. Even museums foolishly reframed their collections. Piles of 17th- and 18th-century frames appeared on the trash heaps of Madison Avenue. Fabulous Victorian plaster frames were destroyed by the thousands. In the 1950s a horse and cart driven by “Frank the Frame Burner” went through the streets of London collecting unwanted 19th-century gilt plaster frames to be stripped of their gold content. A few smart collectors bucked the trend, and slowly the tide turned again. Bonhams auction house in London has held frame sales since 1972 and has sold 20,000 in the past two years alone. “Fifteen years ago any Italian period frame would do for your Bolognese painting,” says frame dealer Gregory. “These days people want a Bolognese frame, and of the same date.”

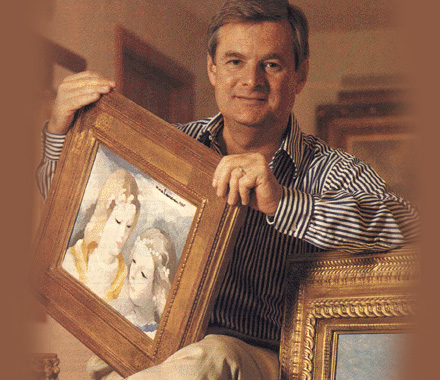

Eli Wilner, a New York frame dealer is generally credited with bringing the period frame back in the U.S. “I found frames in flea markets, in antique shops,” he says. “I could buy them for almost nothing, and I bought thousands. I put them away thinking I’d need them in 30 years, but I ran out in 6 years!”

No more buying for nothing. U.S. dealers now sell most good period frames for anywhere from $5,000 to $50,000. “People want to frame the way the artist would have done it,” says Wilner. ”The market has become much more scholarly.”

Frames have even become art objects in their own right. “They ask me to design ‘nesting formats’ [one frame inside another],” says frame dealer William Adair of Washington D.C.’s Gold Leaf Studios. “The whole wall becomes a montage of ornament – a piece of wall sculpture.”

Jim Dicke, chief executive of Crown Equipment, is a frame lover, who owns over 30 paintings with period frames. His favorite is an elegant, restrained, Spanish-influenced piece, circa 1920, by the Bucks County, Pa. maker Frederick Harer, now on a French painting of the same date. Dicke believes that fine antique frames are still a bargain. “The market has not yet recognized the huge difference between old and new,” he says. “It can cost $15,000 to reproduce a $25,000 period frame, and there’s just no comparison.”

Dealers Wilner, Henry Heydenryk, Julius Lowy and Guttmann Picture Frame Associates (all of New York City) and Gold Leaf Studios have thousands of great examples in stock. Wilner just co-authored American Antique Frames, the first price guide in the field (Avon, $15). The International Institute for Frame Study in Washington, D.C., a nonprofit archive will provide on-line information on flames next year.

Expect this market to heat up a lot more after March 2001, when Washington’s Renwick Gallery mounts an exhibition – working title, “American Frames” – featuring pieces between 1870 and 1940.