All eyes on Eli

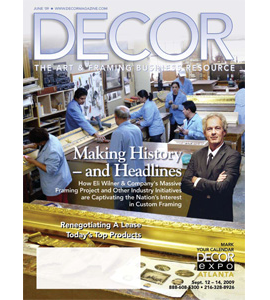

Eli Wilner & Company Has Captured The Nation’s Interest in Custom Framing Through a Massive Framing Project for the MET. DECOR Contributor Baer Charlton, CPF, Delivers All The Details on the Gallery’s Biggest-Ever Undertaking. DECOR Magazine The Art & Framing Business Resource June 2009 By Baer Charlton, CPF

Known today as the foremost American authority on period framing, Eli Wilner has certainly come a long way from his beginnings. There was a time early in his career that one might find him active in the pursuit of longlost artworks through alley skulking, dumpster diving and perusing tag sales in the mountain regions of New York and New England. Motivated by a strong passion for custom framing, he worked his way up, founding Eli Wilner & Company in New York City in 1983. Specializing in American and European frames from the 17th through mid-20th centuries, the company today involves twenty-five highly skilled craftspeople, including 15 frame conservators.

Throughout the years, Wilner and his staff have added an impressive array of jobs—including projects for the White House, Smithsonian and Metropolitan Museum of Art (MET) in New York—to the company’s resume. With each one, the company has further established itself as an authority in the framing world. Helping to cement that status is an extraordinary job the team recently tackled—one that’s garnered significant national media attention and has propelled custom framing to the forefront of consumers’ minds. In 2007, the MET selected Eli Wilner & Company to re-frame America’s iconic “George Washington Crossing the Delaware” painting to be unveiled in 2011 in museum’s new American Wing.

“This is a career-defining project—a tour de force that will, this time, stand the test of time and properly house America’s greatest icon,” Wilner says. The real history being made this time around is the sum of all the little things that created the opportunity to recreate the proper framing for what arguably could be considered America’s “Mona Lisa.” The painting, by German-born artist Emanuel Gottlieb Leutze, is one most Americans likely recall from their school days of studying Washington and his rag-tag army crossing the Delaware. Not to mention, it’s the second most frequently reproduced art image in America. Somewhat more known for its historical inaccuracies— the not-yet-in-existence-at-thetime design of the American Flag, the fact that the men did not bring horses on the boat and so on—the 21′-long by 12′-tall piece was painted more as a symbolic image than a graphic depiction of that historical journey across the Delaware River during the Revolutionary War in 1776. Leutze had designed a fitting frame with grandeur, grace and symbols that spoke not only to George Washington but of the then young nation in general. By the time the painting was gifted by John S. Kennedy in 1879, the original frame had been lost in the shuffle. In 1980, the painting was rolled as it took up current residence in the MET’s American Wing. There, the painting was framed in what is believed to be its third framing—a plain affair that did nothing for it, according to Dr. Carrie Rebora Barratt, curator of American Paintings and Sculpture at the MET.

“In fact, it minimized it,” she says.

Another contributing factor to the re-framing of the painting was a photograph taken about 143 years ago by the famous photographer Mathew Brady depicting the entire “trophy- style” frame as it hung in all its grandeur at exhibition. Barratt stumbled across the photo while studying an 1864 album of Brady’s Art Exhibition photographs. Through modern photo recomposition and digitization, the details of the design are being reproduced accurately “to within an eighth of an inch,” Wilner says.

For Eli Wilner & Company, this massive undertaking has required some postulation and mockups to determine the correct depth and massing of the 3,000-pound frame because of the two dimensional nature of the original photograph. Producing the moulded parts and carving required dedicating 12 of the staff for more than a year. The framing project commanded much of one floor of the Wilner atelier and was made to disassemble for transport and then reassemble at the museum. As for the painting, it is being cleaned, restored and stored at the museum; rolling it up is not an option this time. Not least of the unique converging parts for this historical undertaking is the person who is responsible for the carving of the basswood frame: Master Woodcarver Félix Terán. An employee of Eli Wilner & Company, Terán comes from a family of woodcarvers in San Antonio de Ibarra, Ecuador.

Even though he was hampered by the lack of true detail in the photograph blowup, Terán dismisses the obstacle as just “a challenge.” His job involved delicately carving the gathered flags, the centercrest American eagle, the crossed cannons, pikes and bayonets of the dramatic symbol draped crest riding 12′ across the top. Terán’s talent shines with the carved wood ribbon below the eagle that flows like silk with its inscription of “First in war, first in peace and first in the hearts of his countrymen”—a line from Henry Lee’s eulogy of Washington in 1799.

The symbolisms of the different artifacts of war in the frame design point to Washington’s accomplishments. The flags furled but not laying on the ground represent that he ended the war victoriously. The cannons represent Washington’s place as a general, and the fact that they are crossed is an indication that he was the supreme commander. The bayonets and spears represent an army, not a naval, admiral. It could be argued that the eagle stands for the country, and/or courage. For the new frame, the gold leaf alone was expected to require more than 12,500 3½” square sheets of leaf. Even before the run-up of gold prices in the recent year, the cost was expected to exceed $12,000. The process has required many hands painting on gilder’s liquor, laying leaf, padding and burnishing in a continuous dance in and out of the 112,500-plus square inches of frame surface.

Much of the running ornament is a cast resin composition that is then applied to the base frame of basswood. Basswood is chosen for its stability in heat and humidity. It is most likely, following current standards of hanging, that the painting will be secured to hidden steel beams buried in the wall, and the frame then will be hung around it. The unveiling of the newly framed painting is scheduled for sometime in 2011 when the MET’s newly renovated American Wing opens to the public. Unlike the former cramped viewing conditions, the gallery renovations will allow for a 150-foot viewing approach to appreciate the full grandeur of the restored painting and the recreated grand “trophy” frame. The occasion is one Wilner and his staff are looking forward to. “I can’t wait to see this installed in 2011,” he says. “I’m counting the days.”

The finished 23-karat gold-leafed “mantle,” or “tribute,” rests in a place of honor until the day of assembly. The symbols are as timeless as some of the crests that were carved atop warriors and other dignitaries in the 15th century. From left, the spears represent ground infantry, as opposed to knights or mounted calvary, with one mounted with a banner denoting George Washington’s personal command of his Army. The partially hidden sword represents the fact that not all of his battles were clear victories. The drum is of a regimental Army instead of a regional or city’s inscription. The shield with its 13 stars and stripes in place of a heraldic blazon or crest represent yet another break from the ways of the “old country” and place this war as a battle of the colonies instead of a single man. The chest is to honor the lengthy war that was not a short scrimmage with reprieves at home, but rather fought from a chest for being away from home for a long time. The spears with tassels symbolize Washington’s “glories” in battles, and the cannon and muskets are a nod to modern times— 1776 modern, that is. The draped flags are by far the most important element, as they are not fallen but furled and are elevated as one would expect of a tired flag barrier. These are the flags of a general who outlived the war, distinguished himself during and after, as is testified in the inscription on the banner. Finally, note the eagle has neither arrows nor olive branch in his claws, as the status of the country was at the time undecided.

This rare look at a massive 12′-long carving still in the raw wood allows for the close examination of Master Woodcarver Félix Terán’s hand work. The size and mass allows for the blend of full embodiment and enhanced base relief.

Baer Charlton, CPF, is an internationally recognized award-winning picture framer, author, writer, teacher, artist and self-described frame nerd. He has lectured on various aspects of the applied arts on five continents and while at sea. His productions are held in collections on four continents and have appeared in such museums as The J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles. He is currently working with architectural leaders to devise a standard for framing in respect to Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) certification. Charlton can be reached at info@framenerd.com.

FAST FACTS THE PROJECT: The MET commissioned Eli Wilner & Company to reframe “George Washington Crossing the Delaware” by Emanuel Gottlieb Leutze

PAINTING SIZE: 21′ long by 12′ foot tall

NUMBER OF PEOPLE WORKING ON THE FRAME: 12

FRAME WEIGHT: 3,000 pounds

ESTIMATED AMOUNT OF GOLD LEAF: 12,500 3 ½” square sheets

TOTAL ESTIMATED COST: $500,000-plus

PROJECT UNVEILING: 2011 in the MET’s new American Wing

MORE INFO: www.eliwilner.com (Eli Wilner & Company); the MET (www.metmuseum.org)

Unlike building a 16′ mid-cockpit sailboat in a basement, a frame this size starts with solving the problem of dismantling, transporting and reassembling 3,000 pounds of future history. This is not a time of rushing willy-nilly, but of patient methodical planning and execution. This is, by the way, not day one, which actually occurred years ago when the logs were first cut, milled and set to dry, similar to the process 160 years ago.

With the half-sized carving (half-leafed to make sure the depth was proper for the correct shadows) as the guide, Master Woodcarver Félix Terán begins “massing” the wing of the final carving. Getting the depth right is the critical reason for the test carvings. An 1879 photograph of the original frame by Mathew Brady was extremely “fl at” and did not show the contrasts typically viewable in a modern photograph. The illusion of depth was missing, so guessing based on experience was backed up with test carvings containing every detail that will appear in the final frame.

The corner shield helps hide much of the magic of the frame’s ability to be disassembled and reassembled. In the original frame, it is believed to have served the same purpose, in some respects, for 150 years. The upper, main ridgeline, along with the second step from the sight or lip, are adorned with a specially cast type of epoxy composition designed to be highly durable over time. Certain elasticity is built in to accommodate the possible expansion and contraction native with such massive timbers, even though basswood is one of the most stable woods to be used in the applied arts. The high-relief nature of the carving in the shield demands the expertise of woodcarving to hold the fine detail and be structurally sound in the delicate sweeps of the Acanthus leaves. In the foreground is a sample of the digitally enhanced sections of the original Mathew Brady photo. The crossed cannons are placed at the bottom of the frame and denote George Washington as the Army’s Supreme Commander.

A total of 12 members of the 40-person Eli Wilner & Company crew were dedicated full time to this project for more than a year. The project used more than 12,500 3½” squares of gold leaf in the finishing process—slightly more than a mile-long yellow-leaf road. (Toto aside, by anybody’s book, that’s a lot of rubbing and burnishing, not to mention going “gold blind.”).

Here, patience and a steady, repetitive hand slowly apply the less than a pound of gold spread 1/250,000th of an inch thick. Later, the burnishing will polish the yellow and gray clay underneath that will also allow the color to influence the gold and enhance the highlights with the yellow or darken for drama the area in gray.

Here, patience and a steady, repetitive hand slowly apply the less than a pound of gold spread 1/250,000th of an inch thick. Later, the burnishing will polish the yellow and gray clay underneath that will also allow the color to influence the gold and enhance the highlights with the yellow or darken for drama the area in gray.

Inch by inch, the mile-plus of gold is burnished to the mirror that makes a well-leafed object appear to be cast of solid gold.

Photographer Mathew Brady shot this picture in 1864 by as part of his Exposition series. Even with enhancing software to rival the CSI or NCIS of TV lore, some details still went undiscovered and therefore are lost to the past. The inscriptions on the shields in the corners were one such detail.